Originally published in Issue 4

Regardless of whether growers refer to using an integrated pest management (iPM) or integrated pest and disease management (iPDM) program, it won’t be successful if they don’t plan it out.

“Ironically, one of the biggest misconceptions greenhouse growers have with controlling pests and diseases is actually related to the success of their control programs,” said Karin Tifft , an integrated pest and disease management (IPDM) consultant. “If growers are doing a good job, it seems simple. But when things go wrong, they can go wrong in a big way.”

Tifft works primarily with greenhouse vegetable growers to develop IPDM programs. While she doesn’t yet have any ornamental plant growers as clients, she said she expects setting up an effective IPDM program for ornamentals would be more challenging because the whole plant needs to look good, not just the fruit. She said that ornamental growers actually have more natural enemies and chemical options than food crop producers.

Photo by Adelyn Photography

“Microgreens and lettuce probably come the closest to selling the whole plant like with ornamentals,” she said. “ The difference is that microgreens and lettuce are such short term crops that there is not a lot of time for pest and disease pressures to build up as much. However, this does not mean proactive treatments, as in the release of natural enemies, are not needed. The greenhouse is never usually empty when growing lettuce and greens.”

Tifft said an IPDM program can incorporate multiple techniques, including cultural, chemical and biological.

“My specialty is what I call Bio-IPDM, biologically-based integrated pest and disease management,” she said. “I focus first on using natural enemies where I can. For the disease aspect, I look a lot at cultural control. This includes the ways disease can be prevented in the first place or limiting the spread and economic losses.”

Managing Greenhouse Diseases

Tifft said managing the greenhouse climate is the best way to manage fungal diseases. “Fungal diseases, in particular, usually have an outbreak due to something going wrong with the climate,” she said.

“Fungal spores, like Botrytis, are always present. But even though the spores are there, there is no disease outbreak.

“Growers have to be sure the greenhouse environment is not conducive to the expression of the disease. It is crucial that growers check their greenhouse environmental settings both by computer and by personal observation at various times during the day, including early morning and at night.”

Tifft said in the case of greenhouse tomatoes and peppers she doesn’t usually recommend making any proactive preventive fungicide applications for Botrytis. She will use them if Botrytis is spreading quickly.

“Disease control with cucumbers can be more challenging,” she said. “Growers should select powdery-mildew-resistant varieties to avoid having to apply fungicides too frequently. There are other cucumber diseases that are prevalent including Didymella bryoniae that causes gummy stem blight and Botrytis.”

Tifft said the greenhouse vegetable growers she is working with are currently applying chemical controls on an as-needed basis. She said for some of them there is the potential to move away from pesticides altogether.

“Growers considering aquaponics, which combines the raising of fish with plants, need to keep chemical applications at a minimum. Most pesticides cannot be used in an aquaponics system. This is a major consideration when growers think about this type of production system. Under these circumstances a grower would want to look at what he can do with cultural controls and natural enemies where there is no risk of anything getting into the water with the fish. This would also be the case with the growing of medicinal plants.”

[adrotate banner=”23″]

Tifft said based on her experience with the typical horticultural and agricultural crops there is going to be a place for pesticides for a long time.

“For vegetable growers it has become self-evident to many of them that they need to break the cycle of pests and diseases by emptying and thoroughly cleaning the greenhouse,” she said. “I have seen several cases where insect or disease problems have gotten out of control and there was no way to manage the problems other than to clear out the greenhouse. This may have occurred because of a change made to the IPDM platform. This could include a sudden drop in natural enemies or application of certain chemicals or because the correct action was not taken in a timely manner. The growers then attempted to do everything they could within the limits of the product labels, but weren’t successful at gaining control.”

Biological controls for insects

Tifft said most of the large greenhouse tomato growers in the United States and Canada are using natural enemies for insect control. She said in most of these operations the use of natural enemies is standard operating procedure.

The use of these biological controls has become easier because they have been well researched,” she said. “ There are effective natural enemies and reliable suppliers with good distribution networks which can deliver the biologicals overnight.”

Tifft said the use of natural enemies can be more difficult for the small grower because the cost of shipping can be prohibitive.

“Most natural enemies need to be shipped overnight,” she said. “For small growers, the cost of shipping may be higher than the cost for the amount of product that’s needed. And there usually is no way for growers to store the natural enemies without dramatically reducing their efficacy. They have to be used right away.”

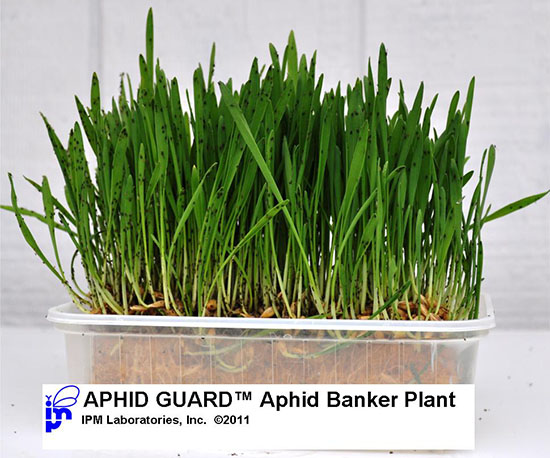

Tifft is currently working with a small vegetable grower to evaluate the option of using banker plants to determine the feasibility of producing a steady supply of natural enemies. She said the banker plant system that is most established is for aphid control. Cereal aphids are introduced into the greenhouse on monocotyledonous plants (i.e., cereal plants such as rye, barley and wheat). The aphids serve as a food source for the parasitic wasp Aphidius colemani. The wasp, which reproduces on the cereal aphids, also feeds on several common greenhouse aphids. “

The banker plants allow for more reproduction and a consistent release of the parasitoids,” she said. “ There is a lot of potential to use banker plants with other hosts and predators.”

Ensuring a successful IPDM program

Tifft said every greenhouse grower, whether vegetable or ornamental, is using some sort of pest management platform, whether it uses chemical, cultural or biological controls. She said the thing that causes most of these programs to fail is quick changes.

“Consider an IPDM platform like a table,” she said. “If one of the legs of the table is kicked out, as in a change from a chemical to biological or biological to chemical platform, without putting in something to prop it up first, such as a new scouting plan or first switching to pesticides with less residual effects on natural enemies, the table will fall and the costs can be high. All of the changes to the platform need to be planned out. Each plan has to be tailored to the needs of the grower, the market, the crops, the climate and state restrictions.”

Photo by Adelyn Photography

Tifft said she prefers that growers looking to incorporate biological controls into their IPDM programs first do trials in a separate greenhouse if possible. “

Ideally a grower would use a separate facility to avoid the effects of pesticide drift from another area,” she said. “Of course, this is not always practical. ere is a learning curve to using natural enemies, but IPDM when done correctly, will save money and lead to increased yields and higher quality fruit that sell for a better price. Reduced pesticide use also leads to fewer worker safety risks and less logistical challenges in terms of re-entry intervals.”

For more: Karin Ti , Greenhouse Vegetable Consultants; http://www.greenhousevegetableconsultants.com.

David Kuack is a freelance technical writer in Fort Worth, Texas; dkuack@gmail.com.