OptimIA economic researchers determined on average, a 1 percent increase in wages would reduce an indoor farm’s profit per square meter for a day of production by 6 cents. A 1 percent increase in the price of electricity would reduce profits by 5 cents per square meter per day. Photo courtesy of Murat Kacira, Univ. of Ariz.

More importantly, will consumers pay a higher price for controlled-environment-grown produce?

Over the last five years, leafy greens have been the “it” crop for indoor farm production. Most indoor farms have started with leafy greens, primarily lettuce, and have looked to expand their product offerings to include herbs, microgreens, strawberries and tomatoes.

The OptimIA project, which is funded by USDA, is studying the aerial production environment and economics for growing indoor leafy greens in vertical farms. While much of the research of this four-year project has focused on managing the environment for vertical farm production, the economics related to this production is a major objective of OptimIA researchers. Based on feedback from commercial vertical farm growers, one of the primary areas of research is to develop economic information, including costs, potential profits, and to conduct an economic analysis to determine the strategies to improve profitability based on that information.

OptimIA researchers at Michigan State University who are focused on the economic aspects of vertical farm production include: Simone Valle de Souza, an ag economics professor; Chris Peterson, an emeritus professor in the Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics; and PhD student Joseph Seong, who is developing his thesis on the economics of indoor agriculture.

“I was invited by the other OptimIA researchers to use mathematical models that take into consideration the biology and technical parameters to determine the potential revenues and costs,” Valle de Souza said. “My team of economists is looking to identify the economic tradeoffs from the implementation of multiple environmental factors that the other OptimIA researchers were optimizing or planned to optimize as part of the project. Our job is to identify the optimal parameters for profitability in controlled environment production. As part of the OptimIA project, we tackled two aspects of economic analysis: production and resource-use efficiency and consumer preferences.”

Maximizing profits

As part of the economic analysis, Valle de Souza considered the variable costs of labor, electricity, seed, substrates and packaging materials. Based on the information collected from commercial indoor farm growers, labor was the largest cost at 41 percent of total variable operating costs, followed by electricity at 29 percent, seed and substrates at 22 percent and packaging materials at 7 percent.

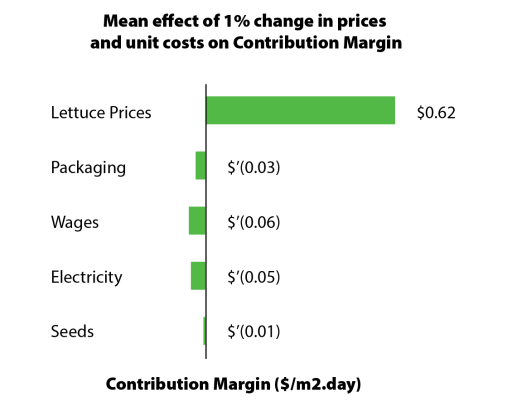

“We did a sensitivity analysis to determine what would happen to profits if wages increased,” Valle de Souza said. “We conducted a series of simulations and determined on average a 1 percent increase in wages would reduce profit per square meter for a day of production by 6 cents. A 1 percent increase in the price of electricity would reduce profits by 5 cents per square meter per day. The contribution margin to profit is normalized on a per square meter per day of production so that we can make comparisons.”

While many growers might look to lower variable costs to increase profitability, Valle de Souza found that increasing the price of lettuce could be the better way to go.

“A 1 percent increase in the price of a head lettuce could increase profits by 60 cents per square meter per day,” she said. “Our analysis showed a revenue maximizing strategy is superior to a cost minimizing strategy. Reducing variable costs could result in savings of 5-6 cents in profit. However, during simulation scenarios that we tried, a revenue maximizing strategy could proportionately increase profits 10 times more by as much as 60 cents.”

OptimIA economists determined a 1 percent increase in the price of a head of lettuce could increase profits by 60 cents per square meter per day. A 1 percent increase in wages would reduce profit by 6 cents per square meter a day. A 1 percent increase in the price of electricity would reduce profits by 5 cents per square meter per day. Graph courtesy of Simone Valle de Souza, Mich. St. Univ.

Optimal length of production

Another part of the analysis done by the OptimIA economic researchers was to estimate the optimum length of the lettuce production cycle.

“In terms of production cycle length, we compared the trade-off between costs from one extra production day and revenues from yield that could be achieved from one extra day of growth,” Valle de Souza said. “We tried to estimate how long growers could allow lettuce plants to grow to take advantage of the fast growth rate the plants experience at the end of a production cycle. Using estimates of plant growth and plant density under an optimized space usage defined by our OptimIA colleagues at the University of Arizona, we found that under specific environmental conditions, day 19 after transplant, or 33 days from seeding, was the ideal harvesting day.”

Even though maximum revenue could be achieved earlier, at day 15 after transplant, costs per day of growth were higher for shorter production cycles. The contribution margin to profit, which was estimated as the difference between revenue and costs in this partial budget analysis, was larger at 19 days after transplant. After 33 days, profit starts to decline because the speed of plant growth rate is not as fast as the increase in costs associated with growing.

“We have determined the economic results from space optimization, estimated optimal production cycle length under given conditions, and the economic results from alternate scenarios of light intensity, carbon dioxide concentration and temperature,” Valle de Souza said. “In collaboration with our OptimIA colleagues, we are now working on a final optimization model that will associate optimal profitability with resource-use efficiency.”

Opportunity to educate consumers

Another aspect of the OptimIA economics research looked at consumer behavior and preferences in regards to indoor farms and the crops they produce. Using a national survey, the researchers determined whether consumers are willing to buy lettuce produced in indoor farms and how much they would be willing to pay for the enhanced attributes of produce grown in indoor farms.

“The survey showed no consumers rejected the innovative technology being used by indoor farms,” Valle de Souza said. “There was a group of consumers who were very supportive of the technology and completely understood what an indoor farm is. Another group of consumers were engaged, but not very convinced of the technology. Another group was skeptical of the claims of indoor-farm-produced leafy greens and were less willing to consume them. This same group said they had no knowledge about indoor farms and how they work.

“There were no consumers who had knowledge about indoor farms and rejected the leafy greens grown in these operations. Some consumers are still cautious given their little understanding about how the production systems work.”

Based on the survey results, Valle de Souza said the indoor farm industry has an opportunity to educate consumers about its production technology.

“The indoor farm industry could promote information materials that explain the benefits of a fully controlled growth environment,” she said. “Growers could explain how this technology eliminates the use of pesticides, how it can improve crop quality attributes, along with the environmental benefits of significantly lower water consumption, reduced land use, and the ability to deliver fresh produce to consumers in urban areas.”

Consumer willingness to pay more

Consumers surveyed by OptimIA researchers indicated they were willing to pay a premium for lettuce with enhanced attributes.

“We tested for taste, freshness, nutrient levels and food safety,” Valle de Souza said. “Consumers were willing to pay a premium for these attributes, especially in urban areas.

“Rural dwellers usually have their own backyards in which they can grow vegetables. They are used to seeing vegetables growing in the soil using sunlight. Rural residents were not as convinced about the need for indoor farms to produce leafy greens. Another interesting survey result was that consumers, in general, are not very decided if they prefer produce grown in indoor farms, greenhouses or outdoors.”

For more: Simone Valle de Souza, Michigan State University, Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics; valledes@msu.edu; http://www.canr.msu.edu/people/simone_valle_de_souza.

OptimIA Ag Science Café #40: Consumer Varieties for Indoor Farm Produced Leafy Greens, https://www.scri-optimia.org/showcafe.php?ID=111156.

This article is property of Urban Ag News and was written by David Kuack, a freelance technical writer in Fort Worth, Texas.